Politics

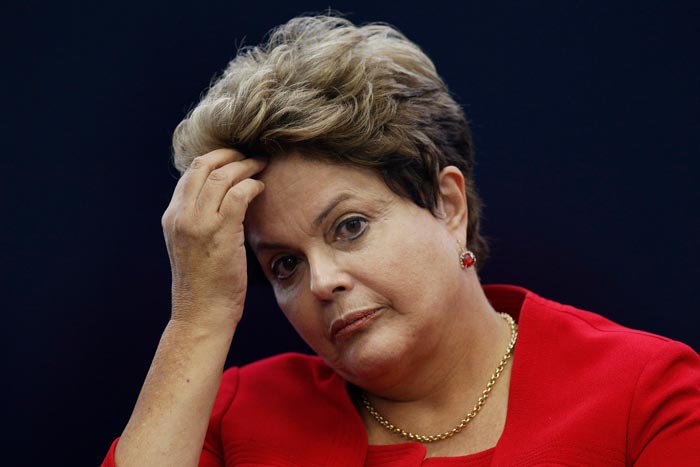

Brazil’s First Female President, Dilma Rousseff Impeached By Brazilian Senate

Michel Temer confirmed as new president after 61 of 81 senators back Rousseff’s removal from office amid economic decline and bribery scandal

Brazil’s first female president Dilma Rousseff has been thrown out of office by the country’s corruption-tainted senate after a gruelling impeachment trial that ends 13 years of Workers’ party rule.

Following a crushing 61 to 20 defeat in the upper house, she will be replaced for the remaining two years and three months of her term by Michel Temer, a centre-right patrician who was among the leaders of the campaign against his former running mate.

A separate vote will be held on whether Rousseff will be barred from public office for eight years.

Despite never losing an election, Rousseff – who first won power in 2010 – has seen her support among the public and in congress diminish as a result of a sharp economic decline, government paralysis and a massive bribery scandal that has implicated almost all the major parties.

For more than 10 months, the leftist leader has fought efforts to impeach her for frontloading funds for government social programmes and issuing spending budget decrees without congressional approval ahead of her reelection in 2014. The opposition claimed that these constituted a “crime of responsibility”. Rousseff denies this and claims the charges – which were never levelled at previous administrations who did the same thing – have been trumped up by opponents who were unable to accept the Workers’ party’s victory.

In keeping with her pledge to fight until the end for the 54 million voters who put her in office, Rousseff – a former Marxist guerrilla – ended her presidency this week with a gritty 14-hour defence of her government’s achievements and a sharply worded attack on the “usurpers” and “coup-mongers” who ejected her from power without an election.

Her lawyer, José Eduardo Cardozo, said the charges were trumped up to punish the president’s support for a huge corruption investigation that has snared many of Brazil’s elite. This follows secret recordings of Romero Jucá, the majority leader of the senate and a key Temer ally, plotting to remove the president to halt the Lava Jato (car wash) investigation into kickbacks at state oil company Petrobras.

While Rousseff was in the upper chamber, her critics heard her in respectful silence. But in a final session in her absence on Tuesday, they lined up to condemn her. As in an earlier lower house impeachment debate, the senators – many of whom are accused of far greater crimes – clearly revelled in the spotlight of their ten-minute declarations. Reflecting the growing power of rightwing evangelism, many invoked the name of God. One cited Winston Churchill. Another sang. Another appeared to be in tears.

“I apologise to the president, not for having done what did, because I could not have done anything else, but because I know her situation is not easy,” claimed a sobbing Janaína Paschoal, one of the original co-authors of the impeachment petition. “I think she understands I did all this in consideration of her grandchildren.”

The result was never in doubt, though Workers’ party figurehead and former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva – who also faces a trial of his own – had lobbied hard until the last moment to try to swing enough senators to avoid impeachment.

At the end of the marathon 16-hour session of speeches, the final nail was hammered in by the former Brazilian footballer Romário, who had been rumoured to be among the few senators who might change their minds and save the president. Instead, he wound up the debate by confirming that he would once again vote for impeachment. “It’s a sad moment when you decide to remove a president,” he told the chamber. However he said he was convinced that Rousseff had committed a crime of responsibility.

Ahead of the verdict, senator Vanessa Grazziotin, of the Communist Party of Brazil, arrived with a sense of resignation. “I’ve worn a mixture of red [for the Workers’ party] and black because today is a day of mourning,” she said. “I’m going to cry.” However, she and other Rousseff allies hoped they could minimise Rousseff’s punishment.

The final result was comfortably more than the two-thirds (54 seats) needed to finalise the president’s removal from office.

Workers’ party senator Lindbergh Farias said the president’s accusers were cowards. “It’s amazing how everyone who didn’t have the gall to look Dilma in the eyes spoke so bravely today in her absence,” he tweeted.

The musician and democracy activist Chico Buarque, who was among Rousseff’s supporters in the gallery, said the debate was rigged against her. “If the game were clean, she would have won,” he told local media.

Others noted that Rousseff’s removal from office less than halfway through her mandate reinforced the impression that the country’s political class remains uncomfortable with democracy although more than 30 years have passed since the end of Brazil’s military dictatorship. Only two of the last eight directly-elected presidents have completed their terms. Two have been impeached, one removed in a military coup, one killed himself, one died before taking power and another resigned.

It also marks a dramatic downfall of a woman who was once one of the world’s most popular politicians with approval ratings of 85%. But she had struggled with a hostile congress and a dire financial climate. When Rousseff took office in January 2011, the economy was growing at a quarterly clip of 4.9%. It has been downhill ever since and she leaves the presidency with output shrinking by 4.6% though this is partly because the price of Brazil’s oil exports is now below half of its peak in 2011.

Rousseff’s achievements in office were mainly an expansion of equality policies put in place by her predecessors, particularly the bolsa familia poverty relief program, which now reaches almost 14 million households.

Thanks to affirmative action and wider access to higher education, university enrolments jumped 18% during her first term. Since 2009, 2.6 million homes have been delivered by the government housing program – Minha Casa Minha Vida. But her record in other key areas is mixed. After falling in her first two years in power, deforestation of the Amazon has started to rise again. Her replacement has a lot to do.

Temer – who was widely criticised for appointing an all-male, all-white cabinet when he took power on an interim basis in May – was due to be sworn in again on Wednesday afternoon and is set to continue until the next presidential election in 2018, when he has promised he will not stand.

Shortly after the ceremony, he is due to fly to China to attend the G20 summit in Hangzhou, where he will hope to restore some of the credibility of an administration that has been battered by accusations of treachery and three ministerial resignations due to corruption scandals.

He has promised to introduce austerity measures that will restore Brazil’s credit ratings, which under Rousseff fell to junk levels. This is popular with investors, but not with the public. His approval ratings are only a fraction above those of his predecessor and he was roundly booed during the Olympic opening ceremony.

During the final stages of the senate trial, there was no repeat of the mass rallies in Brasilia that marked earlier stages of the process. However, a small group of Rousseff supporters staged a candlelit vigil in the main esplanade. Bigger protests have been seen in other cities this week. In São Paulo anti-impeachment protesters and riot police clashed on Monday night. Demonstrators claim the security forces made excessive use of tear gas and percussion grenades in what they fear will be a precursor of more clampdowns on opposition. Police claimed the protesters – many from the Landless Workers’ Movement – blocked roads and detonated a home-made bomb.

Follow us on social media:-

Celebrity Gossip & Gist1 day ago

Celebrity Gossip & Gist1 day ago“The money wey dem pay me don expire” – Moment Burna Boy stops his performance at the Oando PLC end of the year party (Video)

-

Economy1 day ago

Economy1 day agoGoods worth millions of naira destroyed as fire guts spare parts market in Ibadan

-

Celebrity Gossip & Gist10 hours ago

Celebrity Gossip & Gist10 hours agoMoment stage collapses on Odumodublvck during concert performance (Video)

-

Economy10 hours ago

Economy10 hours agoPresident Tinubu cancels Lagos engagements in honor of food stampede victims